Week three of studying for the OSCP has been a step up in terms of difficulty. If you want to catch up on the story so far, here are the summary posts for week 1 and week 2. The modules I was able to cover this week were 8 and 9, Web Application Attacks and Introduction to Buffer overflows.

The common thread between these two subjects is the focus on input sanitation exploits. Input sanitation is when a field that a user can control is verified to be in the proper format. This can mean checking file type, length, character set, etc.

The idea is that if these protections are not put in place in web fields or inputs to programs, a malicious actor can probably find an exploit that will cause an app to crash, information leakage, or code execution. Input sanitation should be done on the frontend and backend! Defense in depth is important!

There are more thorough explanations out there but I want to narrow down the scope of this post. I’m going to focus explicitly on web attacks and creating a reasonable methodology for trying to find exploits that rely on lack of input sanitation.

Step 1 - Information Gathering

The first thing I’m going to try to identify is the technology that runs the web application stack. A simple nmap scan can probably tell me what to expect. The four elements in a web stack that I’m looking for are:

Operating System (Windows/Linux)

Web Server Framework (Apache,

Programming language( PHP, JavaScript, etc.)

Database (MySQL, NoSQL, Microsoft SQL)

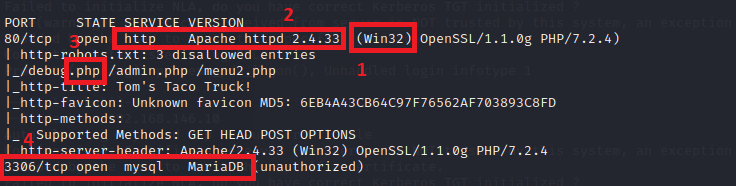

The nmap scan I performed:

nmap -v -p 80,3306 -A 192.168.146.10

The results:

nmap scan results of web server

I’ve marked up the results. From this information, we know that this is a Windows server, running Apache, programmed in PHP, and uses MySQL for a database.

If you’re a web developer, this is probably immediately recognizable. This is the web stack known as WAMP - Windows, Apache, MySQL, and PHP. Spoiler: this is a XAMPP server. X being any OS platform, Apache, MySQL, PHP, and Pearl. For our purposes, that doesn’t make much of a difference.

Here is a list of web stack technologies I found. While not all encompassing, it certainly should cover most of the web apps intended for this course.

To be honest, I’m cheating a little on my nmap scan. I knew that the web server ran MySQL so I checked to see if it showed up on the default port. Here’s a handy dandy link to common Web App/ Database port numbers. Helps narrow down the scanning.

Step 2 - Map the Site and Find User Input Fields

Besides the obvious manual way of mapping out the site and making a list of important areas, it is always worth checking if the webserver has a [URL]/robots.txt or [URL]/sitemap.xml. Either of these resources can be used to find. In the nmap scan results above, we see that robots.txt has been detected and there are three PHP pages to explore. I would also highly suggest using the dirb tool to perform a thorough scan of the site URLs.

Between the robots.txt page and clicking around through the menus at the top of the screen, I was able to find 9 different pages on the site. I’ve included screen shots below of those different pages.

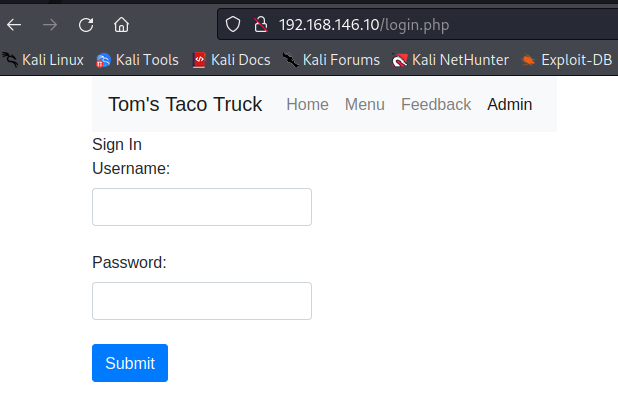

Login page

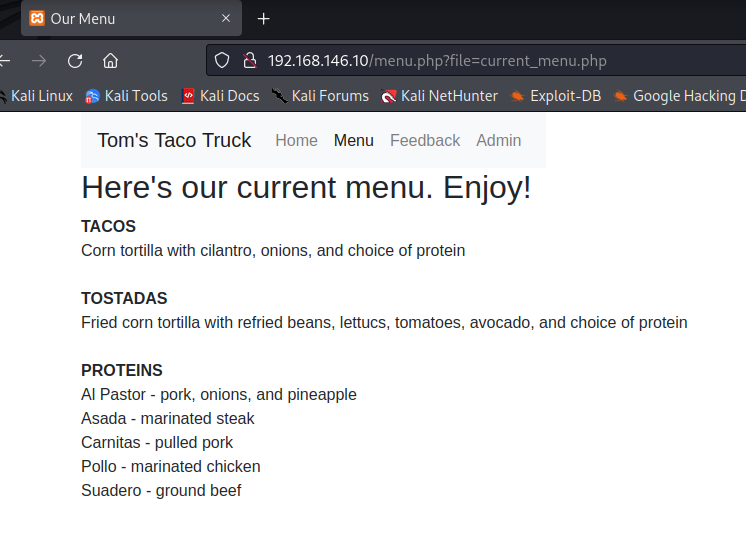

Menu page

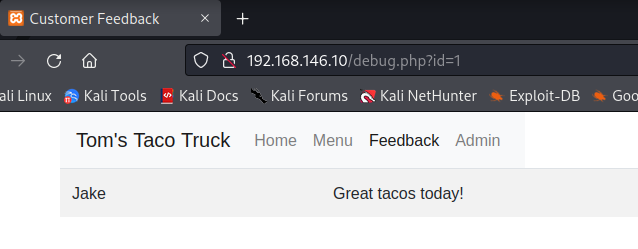

Debug page

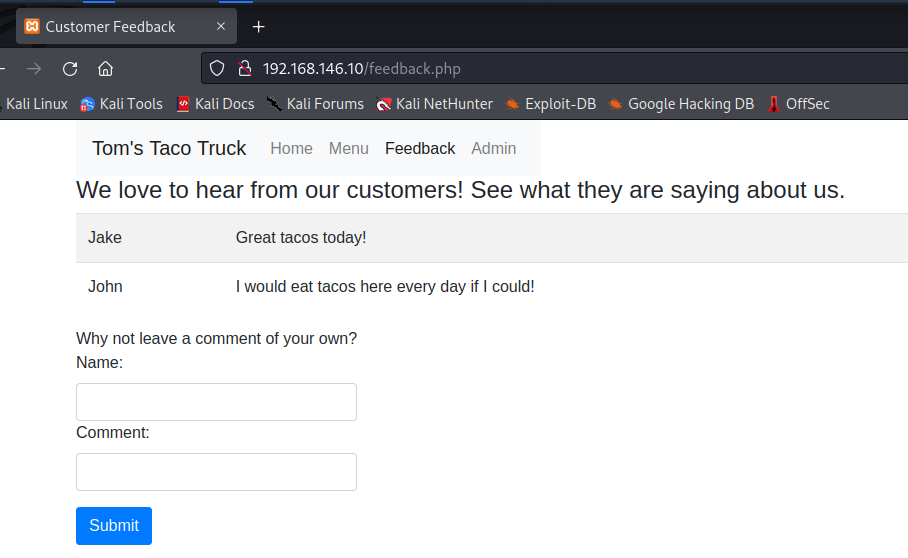

Feedback page

From these pages, here are the user input fields:

Username and Password text fields

URL File path/ID number

Name and comment text fields

The only other major user inputs I can think of off the top of my head would be file upload or a search bar. The fields I’ve listed are still a little too detailed for being able to apply in a broader context. Here is a better way to think of user input fields:

Unstructured text: Username/passwords, comments, search bars, etc.

URL: File paths, ID numbers

File uploads: Submit documents, jpgs, pdfs

Step 3 - Determine the exploit you want to try

This step requires the knowledge of why an exploit would make sense for a field. This should become intuitive after awhile, but I’m writing everything out now so that I can keep this as a quick reference guide.

Unstructured text

SQL Injection

XSS

URL File path

SQL Injection

Directory/Path traversal - be sure to keep in mind the server OS

Local File Inclusion(LFI)

Remote File Inclusion (RFI) - highly unlikely

Data scrape if field is numerical (e.g. id=1)

File uploads

Code execution

Directory/Path Traversal for execution

Working through the modules, I find out that this website is storing plaintext username and passwords in an unencrypted database. Even I know that’s afoul.

Step 4 - Start Googling

At this point, I’m turning to Google to find out the exact way to perform a remote file inclusion or log poisoning on a machine. It is useful to know off the top of your head the exact MySQL exploit tests on an input field, the point of this post is to say that getting to that point is (usually) the hardest part.

At this point, you can blindly guess or things may come with experience. If there is a search query - start with a SQL injection before XSS.

Kind of anticlimactic.

On a side not, if you see a website like this, just email the admin this gif.

Now that we’re getting towards the end of this post, time to throw in a bunch of caveats. Modern web apps are exponentially more complicated than the page based sites used to teach most examples. I’m not a web developer and I don’t want to butcher an explanation, so all I’ll say is do not expect any simple attacks to work on a website made in the last few years.

But, the internet isn’t exactly speedy to adopt all the best security practices or patches. Web development is hard! And maintaining a site for many years is even more difficult. Sites used on internal corporate networks not exposed to the internet may have these vulnerabilities because they haven’t been updated in years. Shoutout Substack so I don’t have to deal with maintaining my own server/blog, albeit at the cost of customizability.

I work more on the embedded devices side of things, so this is by no means my area of expertise. But I’m going to be using this approach because it keeps me focused and prevents me from bouncing around too much.

There are absolutely automated tools for this kind of attack. An example of this is SQLmap, which automates a good part of the actions above. But I can’t use that on the OSCP exam, so I never really explored it all too much. See my post from last week on not

This is my first post diving deeper on a technical subject, so I apologize to all the people smarter than me that read this and thought “what an idiot.” Tell me what I got wrong! And come back next week.